John Dalton Experimental Atomic Model

- 1.

The Humble Beginnings of John Dalton’s Scientific Curiosity

- 2.

What Was John Dalton’s Major Discovery?

- 3.

Dalton’s Atomic Theory in Simple Words (No PhD Required)

- 4.

How Did Dalton Use Experimental Evidence to Support His Theory?

- 5.

The Main Idea Behind Dalton’s Theory: A World of Tiny Spheres

- 6.

Colorblindness and Chemistry: How Personal Quirks Shaped Science

- 7.

Limits and Legacy: Where Dalton Got It Wrong (and Why It Still Mattered)

- 8.

From Classroom to Canon: How Dalton’s Work Spread

- 9.

Modern Echoes: How Dalton’s Ideas Live in Today’s Labs

- 10.

Exploring Further: Resources for the Curious Mind

Table of Contents

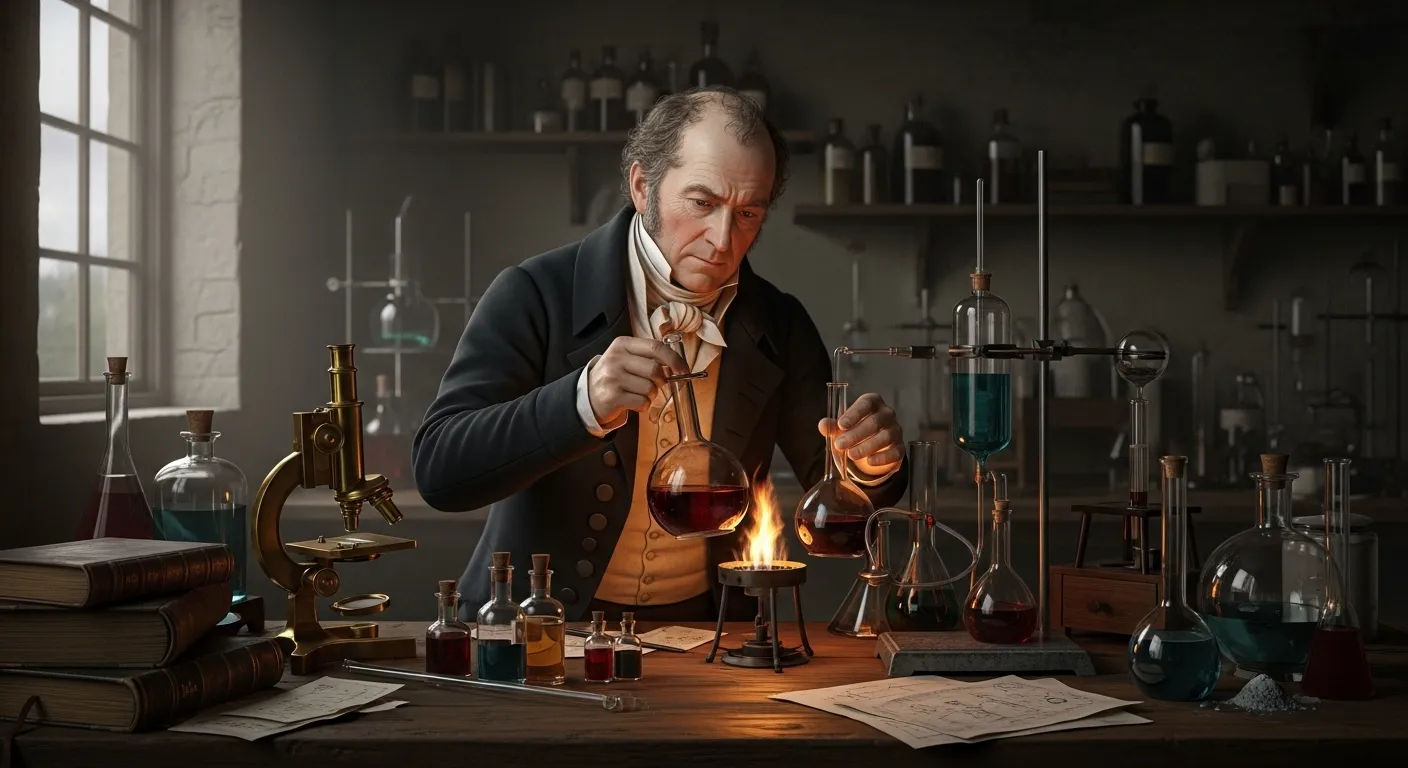

john dalton experiment

The Humble Beginnings of John Dalton’s Scientific Curiosity

Born in 1766 in Eaglesfield, Cumbria—a village so small you’d blink and miss it—John Dalton didn’t have silver spoons or Oxford degrees. He taught school by day, scribbled meteorological logs by night, and measured rainfall like it held the secrets of the universe (which, in a way, it did). His early fascination with weather led him to study gases, and that’s where the magic began. By observing how different gases mixed without reacting, he started questioning: What if air isn’t one thing, but many tiny particles coexisting? That hunch—born not in a fancy lab but in a damp English classroom—planted the seed for what would become his groundbreaking john dalton experiment. Funny how genius often starts with a simple “huh?”

What Was John Dalton’s Major Discovery?

Let’s cut to the chase: John Dalton’s biggest breakthrough wasn’t a single eureka moment—it was a whole new way of seeing matter. Through careful measurement of gas behavior and chemical reactions, he proposed that all elements are made of indivisible, indestructible atoms, and that compounds form when atoms combine in fixed ratios. This idea—now known as atomic theory—was radical in 1803. Before Dalton, alchemy and vague “principles” ruled chemistry. After him? Everything had structure. His john dalton experiment with gases like oxygen, nitrogen, and carbon dioxide showed consistent mass ratios during reactions, proving that atoms weren’t just philosophical musings—they were measurable, predictable, and real.

Dalton’s Atomic Theory in Simple Words (No PhD Required)

Imagine Lego bricks. Each color is a different element—red for oxygen, blue for hydrogen, green for carbon. You can’t break a single brick apart (they’re “indivisible”), and when you snap them together, they always follow set patterns: two blues + one red = water. That’s Dalton’s atomic theory, plain and simple. In his own words (well, paraphrased):

“Elements consist of tiny particles called atoms. Atoms of the same element are identical; atoms of different elements differ in weight and properties. Compounds form when atoms join in fixed, whole-number ratios.”

His john dalton experiment provided the first experimental backbone for this model—turning abstract philosophy into hard science. No mysticism, no hand-waving—just scales, flasks, and stubborn precision.

How Did Dalton Use Experimental Evidence to Support His Theory?

Dalton wasn’t just theorizing—he was weighing, recording, and cross-checking like a chemist possessed. One of his key john dalton experiment setups involved analyzing the composition of gases and compounds. For instance, he found that carbon dioxide always contained 2.67 parts oxygen per 1 part carbon by weight—no more, no less. Similarly, water consistently showed an 8:1 oxygen-to-hydrogen mass ratio. These fixed proportions screamed “atomic combinations!” He even created the first table of atomic weights (using hydrogen as 1), though some values were off due to limited tech. Still, the pattern was undeniable: nature loved whole numbers. And that became the bedrock of his atomic theory—built not on guesswork, but on repeatable, quantifiable john dalton experiment data.

The Main Idea Behind Dalton’s Theory: A World of Tiny Spheres

At its core, Dalton’s vision was elegantly mechanical: atoms are solid, indestructible spheres—like microscopic marbles—that retain their identity through chemical changes. Unlike later models (looking at you, Thomson and Rutherford), Dalton’s atoms had no internal structure; they were the ultimate building blocks. His john dalton experiment with gas solubility further supported this—showing that each gas dissolved independently in water, as if unaware of others’ presence. This “billiard ball” model might seem naive today, but in an era before electrons or nuclei were imagined, it was a masterstroke of logical inference. And let’s be real—it got the conversation started.

Colorblindness and Chemistry: How Personal Quirks Shaped Science

Here’s a fun twist: John Dalton was colorblind. Not just “can’t tell navy from black” colorblind—he saw pink where others saw green. Instead of ignoring it, he studied it, publishing a paper in 1794 titled “Extraordinary Facts Relating to the Vision of Colours.” Though his theory (that his eyeball fluid was blue-tinted) was wrong, his self-experimentation set a precedent. This same meticulous curiosity bled into his john dalton experiment work—where observation, however odd, demanded investigation. Legend says he asked his eyes be examined after death to solve the mystery (they were—and confirmed normal). Point is: Dalton’s willingness to question everything, even his own senses, fueled his scientific rigor. And that spirit lives in every john dalton experiment replication today.

Limits and Legacy: Where Dalton Got It Wrong (and Why It Still Mattered)

Let’s not pretend Dalton was infallible. His john dalton experiment conclusions had flaws: he thought atoms of the same element were identical in mass (we now know isotopes exist); he assumed water was HO, not H₂O (oops); and he rejected the idea of diatomic molecules (so oxygen = O, not O₂). But here’s the kicker: even his errors advanced science. When Avogadro later proposed molecular theory, it was because Dalton’s framework existed to challenge. Science isn’t about being right forever—it’s about building ladders others can climb. And Dalton handed us the first rung.

From Classroom to Canon: How Dalton’s Work Spread

Dalton didn’t shout from rooftops—he published quietly in 1808’s A New System of Chemical Philosophy. Yet within decades, his atomic theory became chemistry’s lingua franca. Why? Because his john dalton experiment methods were transparent, replicable, and rooted in measurement. Teachers could demonstrate fixed ratios with simple lab gear; industrial chemists could predict reaction yields. Suddenly, chemistry wasn’t artisanal guesswork—it was engineering. By the 1860s, Mendeleev used atomic weights (refined from Dalton’s tables) to build the periodic table. All because one man in Manchester kept weighing gases and asking, “Why?”

Modern Echoes: How Dalton’s Ideas Live in Today’s Labs

Walk into any high school chem lab today, and you’ll see Dalton’s ghost hovering over the balance scale. The concept of molar mass? Rooted in his atomic weights. Stoichiometry? Built on his fixed-ratio principle. Even analytical techniques like mass spectrometry owe a nod to his insistence that elements have characteristic masses. Sure, we’ve smashed atoms open and found quarks dancing inside—but the foundational idea that matter is granular, countable, and rule-bound? That’s pure john dalton experiment DNA. As chemist J.R. Partington once said: “Dalton made chemistry a science.” And he did it with pen, paper, and patience.

Exploring Further: Resources for the Curious Mind

If Dalton’s story has you itching to dive deeper into the atomic age, you’re in luck. Start at the homepage of Onomy Science for a full sweep of science history and breakthroughs. Fancy more biographies? Our Scientists category unpacks everyone from Lavoisier to Curie. And if you’re curious how Einstein later revolutionized atomic theory with Brownian motion, don’t miss our piece on Bert Einstein Atomic Theory Legacy (yes, we cheekily call him “Bert”—he’d probably chuckle). Because understanding the john dalton experiment isn’t just about the past—it’s about seeing how one quiet mind can rearrange the universe.

Frequently Asked Questions

What was John Dalton's major discovery?

John Dalton’s major discovery was the development of the first modern atomic theory, based on experimental evidence from his john dalton experiment work. He proposed that all matter is composed of indivisible atoms, that atoms of the same element are identical in mass, and that chemical compounds form through fixed ratios of different atoms—laying the foundation for quantitative chemistry.

What was the main idea theory experiment description of John Dalton?

The main idea of John Dalton’s theory was that elements consist of tiny, indestructible atoms that combine in simple whole-number ratios to form compounds. His john dalton experiment involved precise measurements of gas reactions and compound compositions, revealing consistent mass proportions that supported his atomic model—effectively transforming chemistry from qualitative speculation into a predictive science.

What is Dalton's atomic theory in simple words?

In simple terms, Dalton’s atomic theory states that everything is made of tiny, unbreakable particles called atoms. Atoms of the same element are alike; atoms of different elements are different. When elements combine to make compounds, they do so in fixed, simple ratios—like building blocks snapping together. This idea emerged directly from his john dalton experiment data on chemical reactions and gas behavior.

How did Dalton use experimental evidence to support his theory?

Dalton used meticulous experimental evidence from his john dalton experiment—analyzing the mass ratios in which elements combined to form compounds (e.g., water always had 8g oxygen per 1g hydrogen). He also studied gas solubility and pressure, noting consistent behaviors that suggested discrete particles. These repeatable, quantitative results allowed him to propose atomic weights and fixed combining ratios, turning atomic theory from philosophy into testable science.

References

- https://www.chemheritage.org/discover-and-learn/scientific-biographies/biographies/dalton-john

- https://www.britannica.com/biography/John-Dalton

- https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/ed079p1305

- https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/10.1098/rsnr.2016.0023